Yellowstone Rock: Made by Volcanic Hot Springs

Note: This article is part of a series about American quarries. If you work for a quarry that’s a member of the Natural Stone Institute and you’d like your quarry to be featured here, contact Amy Oakley. Thank you!

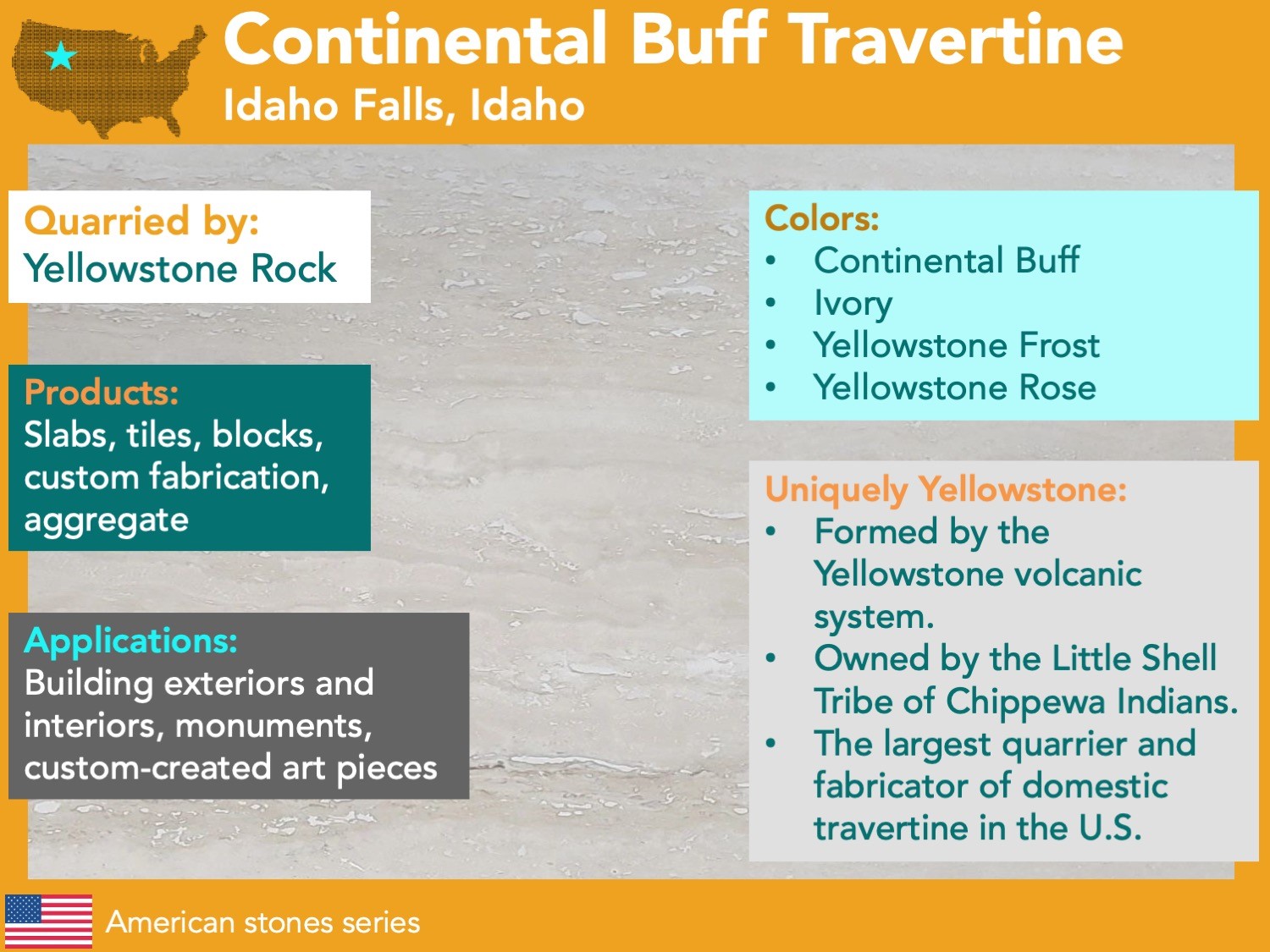

Type of Stone: Travertine

Quarried from: Idaho and Montana

Not too far below the ground, the Yellowstone supervolcano’s persistent geothermal heat stokes iconic geysers, boiling mudpots, and colorful hot springs.

A body of magma resides about 3 miles below the surface of Yellowstone National Park. The hot rock warms the groundwater, which then travels upward along faults, dissolving minerals from the surrounding rock as it passes by. By the time the hot water emerges at the surface, it’s laden with minerals.

Travertine is the most common type of stone made by hot springs. Calcium carbonate is dissolved from layers of limestone rock below and carried upward. As the water flows out of the earth, it cools down and deposits the minerals. Over time, the flowing hot water leaves behind layer upon layer of newly-formed rock in the artistic pattern that makes travertine so treasured.

Tribal ownership

Not far from the park’s border in Montana, an extinct hot spring formed a substantial travertine deposit. It’s been quarried from time to time over the past 100 years, but the quarry took on a renewed life in 2020 when the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians purchased the quarry.

Brian Adkins is a member of the Little Shell Tribe and the tribe’s Economic Development Director. The quarry purchase has been an exciting development for the tribe. The 72-acre parcel contains an abundant supply of stone, and “It’s ours,” says Adkins. “Nobody can ever take it away.”

Expanded production; growing markets

Along with the Montana quarry, the Little Shell Tribe purchased a successful multi-generational, family-owned business with a fabrication shop and two travertine quarries. The fabrication shop is in Idaho Falls, and the quarries are in the Greater Yellowstone area.

This company, formerly known as Idaho Travertine, was owned by the Orchard family for over 40 years. Several members of the family along with many of the employees continue to work at Yellowstone Rock, providing well over 100 years of combined experience working with travertine. Yellowstone Rock is the largest quarrier and fabricator of domestic travertine in the United States. “It’s a great thing for us,” says Adkins.

The tribe has made investments in new saws from Italy which allow faster production from the quarries. “We’ve really gone all in,” explains Adkins, noting that new equipment “has definitely improved our quarrying techniques.”

The fabrication has also been transformed. A new 5-axis CNC saw allows for custom cutting, and a new multi-wire saw can cut multiple slabs at once, which has quadrupled the shop’s slab production rate. Once the slabs are cut, a calibrator is used to grind and flatten slabs so they can be finished to a consistent thickness, ranging from thin tiles to thick slabs. Polishing equipment from Italy completes the job. “The modern machines make so much difference,” says Adkins, noting that the work is far better, quicker, and more profitable than before.

The combination of new ownership, increased investment, and high-quality stone has Yellowstone Rock poised for growth. “The outlook is really good,” says Adkins.

Harmonious colors and finishes

Four different colors are quarried: Ivory, Yellowstone Frost, Continental Buff, and Yellowstone Rose. The color palette ranges from near-white to creamy beige, warm light grey, and even a hint of pink. The colors are easygoing – they blend harmoniously with each other and with just about any architectural style.

The stone can be cut perpendicular to the layering, known as “vein cut,” to reveal travertine’s signature intricate texture and small, slightly wavy layers. Cutting parallel to the layering (“cross cut”) produces a flowing texture with organic, curving patterns.

The material is less porous than a typical “holey” travertine, so it needs less filling and has a smoother look and higher density. Recent testing by the Natural Stone Institute shows the stone is suited to indoor or outdoor applications, even in cold climates.

Expanded fabrication capabilities allow for a variety of surface textures ranging from a satiny smooth polish to a touchable-textured leathered finish, to natural cleft surface.

Italian aesthetic with American origins

The company’s most popular stone is Continental Buff vein cut, which is similar to the Italian Navona travertine but all the better because it comes from right here in the United States. Yellowstone Frost is an ethereal shade of white, with flowing patterns reminiscent of marble.

Travertine from Yellowstone Rock travels from the Northern Rockies to all corners of the United States. The stone has found its way to metropolitan areas like Seattle, Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, and Dallas, and of course it’s equally at home near its native environment in buildings across Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming.

Continental Buff has been used for several notable projects such as the Idaho Supreme Court building, Renaissance Atlanta Waverly Hotel, and the Potter County Courthouse in Amarillo, Texas.

American stone, “a big draw”

Justin Lindblad is the Director of Sales for Yellowstone Rock. He notes that the response to the stone has been strongly positive, especially because it comes from the U.S. “The response has been remarkable,” he says, citing advantages like LEED benefits, cheaper shipping costs, short lead times, and easy access to visit the quarries firsthand.

“To have a domestic travertine product that rivals the Italian travertines has been a big draw,” he says, “that the material is quarried right outside Yellowstone National Park amplifies the interest.”

“I think the biggest challenge so far has just been educating people that a domestic source for travertine exists’” he says. Lindblad is optimistic that as the company gets its message out about its stone and its capabilities, they are ready to accommodate projects large and small.

Adkins concurs, and is eagerly anticipating the next wave of improvements, increased production, and new capabilities, “We’re so dang excited,” he says. “We can hardly wait.”