Coming Full Circle with Super White

My involvement with the natural stone industry began in a distinct moment in 2012. In the midst of a kitchen remodel, I was browsing kitchen discussions on the Houzz website, learning about grout and cabinet hinges and numerous other topics that suddenly were of urgent importance.

Then a fascinating thread scrolled into view, asking, Anyone ever cover their marble with saran wrap for a party? I eagerly clicked into the lively discussion about a Super White countertop that had been etching unexpectedly. Would covering it in plastic wrap be a good solution? The resounding answer was no, it would not.

At that time, Super White was still relatively new on the scene and often mislabeled as a quartzite, leading to disappointment when it didn’t act like one. Hence, the urge to wrap it in plastic.

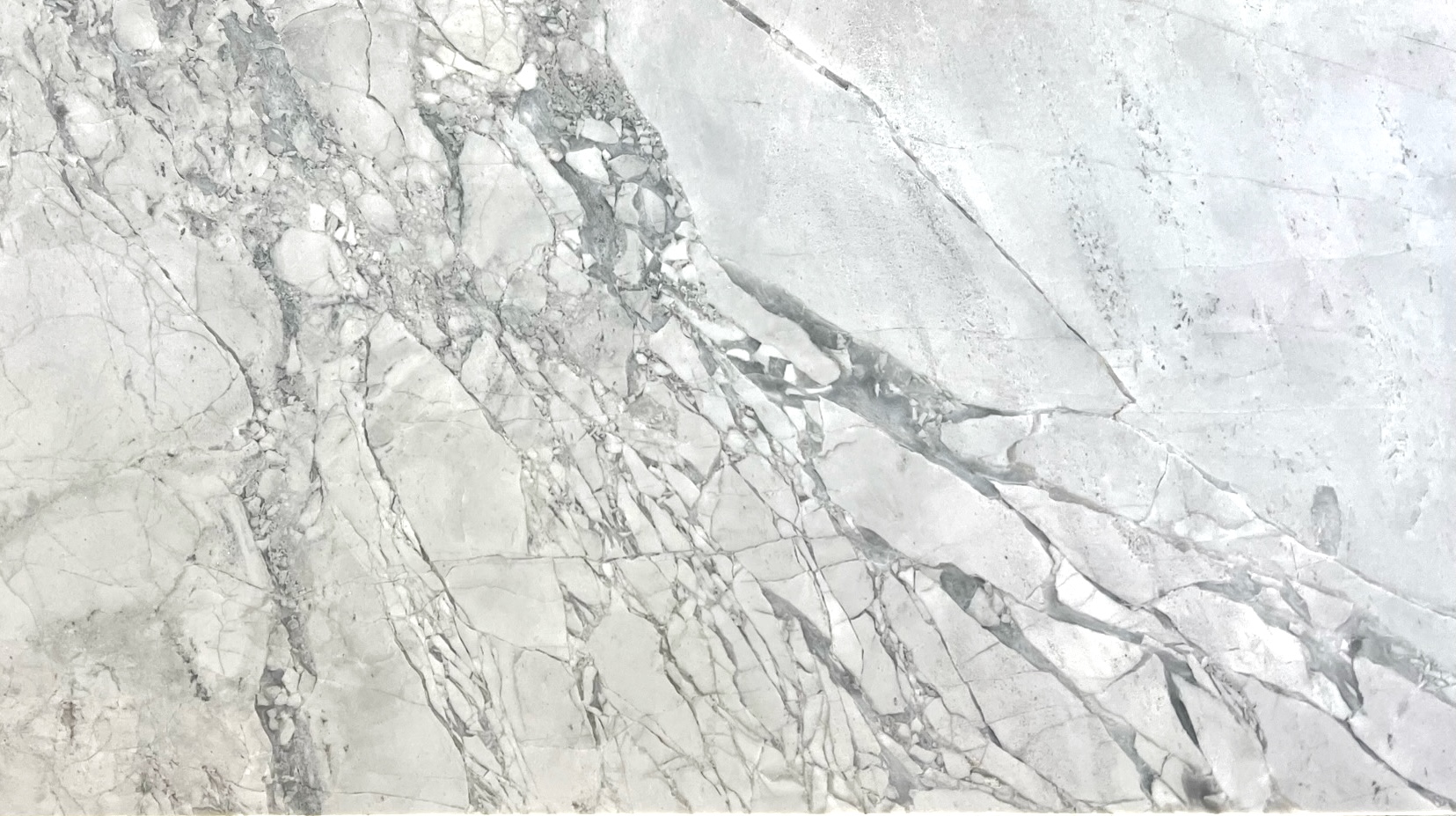

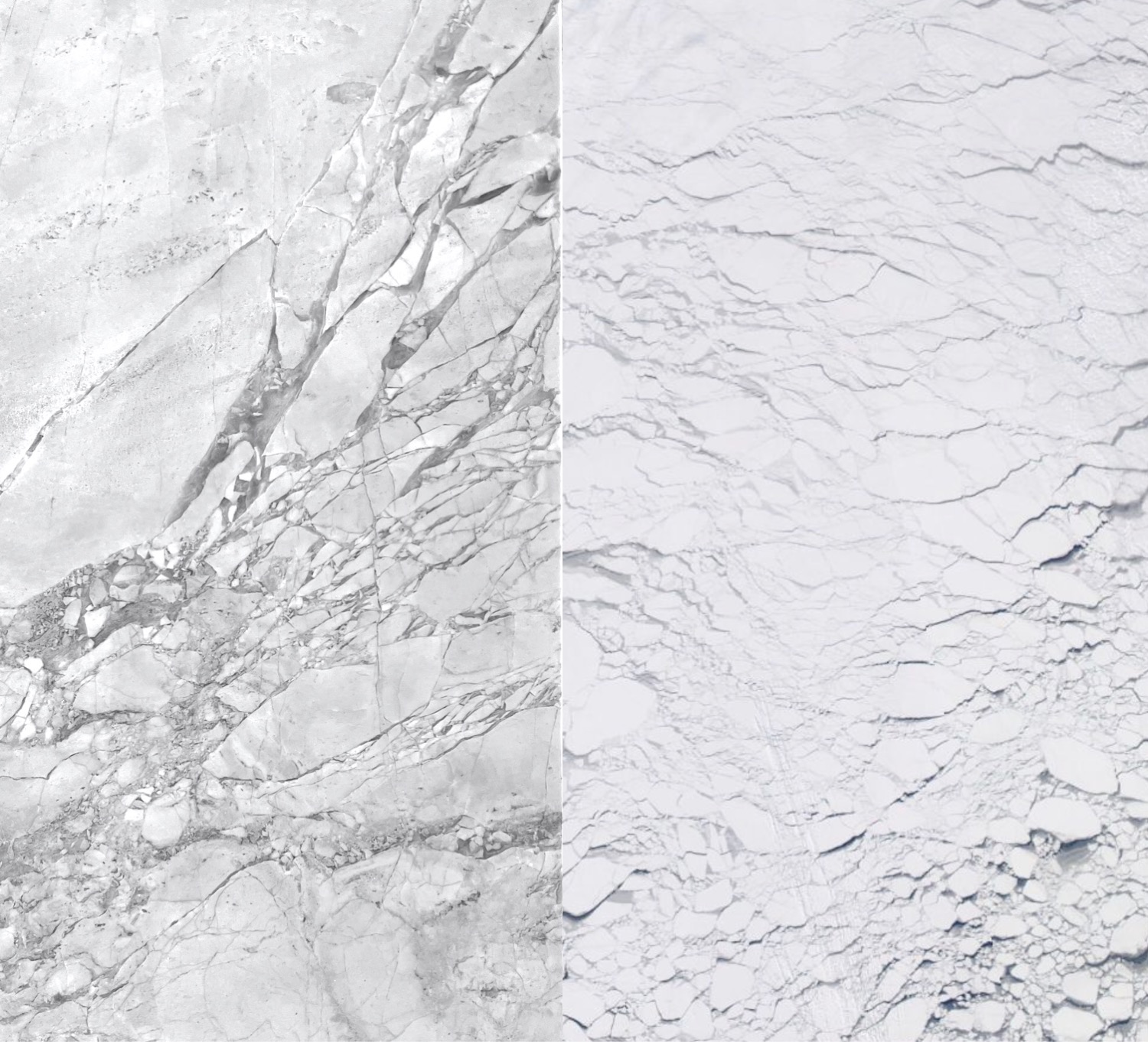

On my next visit to the slab yard, I spotted a slab of Super White. Swoon! That’s one gorgeous stone – a blend of white and cool greys arranged in a dynamic pattern reminiscent of a fractured ice floe. It was immediately obvious why the stone was a superstar, despite the nebulous problem with its identity.

The helpful salesperson gave me a sample and I went home to do some diagnostics. The stone didn’t scratch glass, which ruled it out as a quartzite. I put a single drop of diluted hydrochloric acid on the stone, expecting a slight fizzing action and an etch mark. But nope, the stone didn’t etch. That meant it wasn’t a calcite-based marble. Next up, the test for dolomite: I roughed up an area of the stone with a nail, then put a drop of acid on the bits of powdered rock I’d scraped up. Bingo! It fizzed – the stone is made of dolomite.

Dolomite is similar to calcite but it contains some magnesium in addition to calcium. Compared to calcite, dolomite is slightly harder and it etches more slowly. That makes a dolomitic marble somewhat more durable than “regular” marbles that are made entirely of calcite, but the difference is subtle.

There’s one more complicating factor with identifying Super White. The rock has fractures that are filled with quartz. This happens when the rock breaks underground – usually due to some sort of tectonic stress – and then mineral-rich groundwater fills in the broken parts. Geologists call this texture a “breccia” and it’s what gives Super White its magnificent pattern of white marble fragments floating in a river of grey. These small areas of quartz may have led to the stone being mislabeled as a quartzite, but it’s not a quartzite by any stretch. The rock’s full scientific name is brecciated dolomitic marble.

Marble is a stone that’s been beloved and useful through the ages, but it’s one that warrants careful consideration. The potential for etching and scratching can be a dealbreaker for some, but no problem for others – but either way, people need to be able to make an informed decision. The more that sales reps, fabricators, designers, and homeowners can learn about the properties of stone they’re considering, the happier everyone will be.

I wrote up my findings in a post on Houzz in a thread called The lowdown on Super White, and woke up the next morning to find a half-dozen responses and questions. By the time I’d answered the follow up questions, several more appeared. Who knew that geologic descriptions of countertop stones would be such a hit? The thread soon reached its 150-post limit so I started another. It too quickly filled up so I started yet another, and another. I’d unexpectedly stumbled into a topic that seemed a good match for a geologist who happens to like kitchens.

Before too long I’d found the Marble Institute of America (now the Natural Stone Institute) and a happy collaboration was born. One of our first priorities was to delve into this very topic: The Definitive Guide to Quartzite. The popularity of marble and quartzite led to articles such as Telling White Stones Apart, that aimed to help people sort out the differences between similar-looking stones.

But there was one more element of that original post that was prescient. I wrote, “I swoon every darned time I pass by a slab of white marble. I just love it! But I will have to come up with another place to use it, like as a mantle or a countertop on a china cabinet.”

Fast-forward 12 years, and my dream built-in cabinet and bookcase was being installed, and I could finally carry out that vision. I still stop dead in my tracks every time I come face to face with a slab of white marble. It’s an exquisite material, made all the better because it comes naturally from the Earth. At last, I was admiring these beauties as a customer, not a scientist.

I checked out many different slabs, but honestly, there was never a doubt in my mind that I’d end up with Super White. It also happened to be the only white stone that my husband liked. I was able to find a remnant piece with a brilliant pattern of fracturing that was gloriously similar to the satellite images of sea ice that I use in my science writing for NASA. I stood in front of the slab and ran my fingers over the leathered surface, appreciating the texture of the marble blocks floating within the icy quartz veins. I felt so very lucky that it was finally time for a piece of glorious white stone of my own.